VOICES: Latin@s, Hispanics, Latinx: ¡Si! To All of it!

By Rev. Lydia Muñoz – It’s fair to say that most people when asked to describe Latinos in the United States would probably be limited to naming a few celebrities and athletes, and a couple of great restaurants they visited on Cinco de Mayo. Most people do not even begin to understand the complexities and the vast diversity of the Latino population in the United States. Just take for example the many ways we are referred to as a group in this country: Latino, Hispanic, Spanish-American, Hispanic-American, and over the past several years Latinx. We have always been categorized as one kind of community because of our common tongue and our ties with Spanish colonialism, but let’s break this down a little bit.

After the Mexican American War concluded in 1848, the term Hispanic or Spanish American was primarily used to describe the Hispanos of New Mexico within the American Southwest. The 1970 United States Census controversially broadened the definition to “a person of Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, Dominican, South or Central American, or other Spanish culture or origin, regardless of race”. This is now the common formal and colloquial definition of the term within the United States, outside of New Mexico. This is the same definition as the U.S. Census Bureau and the Office of Management and Budget use interchangeably for both Hispanic and/or Latino.[1] The term “Latino” is a condensed form of the term “Latino-americano”, the Spanish word for Latin American, or someone who comes from Latin America. However, it also includes a person of Brazilian descent in this definition because Brazil is part of Latin America and has similar colonial history with Spain and Portugal just as other countries of Latin America.

The term Latinx gained currency among some in the 2010s. The adoption of the X was mostly in part to the more recent work of inclusion by LGBTQI activist within the Spanish-speaking world to eliminate the gender binary so common in the Spanish language. It especially took on more support after the Pulse Nightclub shooting in Orlando, Florida in June of 2016. However, a 2020 Pew Research Center survey found that about 23% of Latinos use the term (mostly women) and 65% said it should not be used to describe their ethnic group, and as you can imagine both numbers continue to change given the growth of young Latinx millennials. So, even within the diversity there’s diversity. Which is precisely my point. We are not all the same!

Hispanic, Latino, Hispanic-American, Latinx so many ways we have been identified in this country and, all of them speak volumes about the violent history of colonization of the people that inhabit Latin America and the Caribbean. On our skin, in the texture of our hair, the mixture of our foods, the variety of music and rhythms we share, the accents and idioms that you can hear even as we speak Spanish or Portuguese, both the language of our colonizers, all of it is a living witness to what our people have lived through and the complexities of our diversity or what Jose Vasconcelos called “la raza cósmica / the cosmic race.” We are as diverse as any other group of people and no matter how hard the Census Bureau or political pollsters and demographers have tried to narrow us down, repeatedly we are often misrepresented and oversimplified as a group of people easily defined and predicted.

This diversity is also reflected in our theological understandings, and nowhere is this more visible than in our current debate in the United Methodist Church. As groups continue to assemble their teams and sides considering the impending and predicted schism of the denomination, the common narrative is that most Latinos/Latinx folks in the denomination will end up leaving the denomination because they tend to lean more conservative. Although that may be true in certain conferences, it is probably not a good thing to place your bets completely on either side. Just as every family must make decisions in their lives, so too every single Latino/Latinx congregation in our denomination is having a series of deep conversations primarily focused on our very survival within this denomination. The diversity of our theological understandings is a testament to our deep commitment to critical thinking and analysis, because believe it or not we are capable of these things and the continued burgeoning of theological critical thought that brought about the “browning of Jesus” long before it was a popular thing to say. People like Gustavo Gutierrez and his pedagogical lens toward the poor and Virgilio Eliozondo and his mestizo Jesus; Ada Maria Isasi Diaz and Elsa Tamez putting a name on the mujerista theology and its “lucha.” As well as the sermons and sayings of one of the most revered and sacred icons of Latin American struggle, Archbishop Oscar Romero. All of these continue to challenge the church to read, as Dr. Miguel de la Torre and Dr. Loida Martell constantly remind us to read with Latino eyes and against the grain.

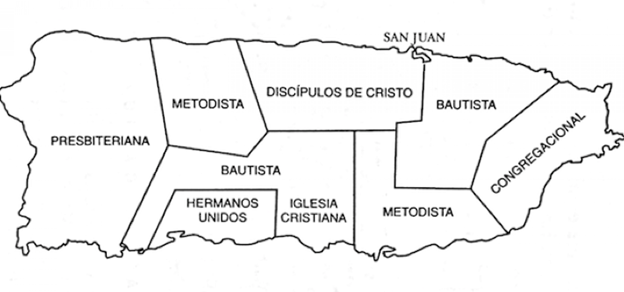

We shouldn’t be surprised by this diversity of theological thinking because all of it was imported to us by the great missionary endeavor to help Christianize Latin America during its colonial conquest and later on through protestant missionaries. For example, in my little island of Puerto Rico alone that is only 110 miles long by 40 miles wide, it was literally divided among the mainline protestant denominations after the Spanish American war of 1898.

As the United Brethren Church put it, this was an attempt to keep each other from “stepping on each other’s toes in this new mission field acquired through the war.” It also served as a launching pad for them, “to inaugurate a work that assures the Americanization of the island, similar to the work of welcoming individuals into the joys and privileges of being a Christian disciple…we should inaugurate schools that will reach hundreds of children who can be formed through these institutions in the responsibilities of being an American citizen.”[2] Their words not mine. This same “missionary work” occurred across Latin America. Brazil, which was largely a Catholic country before the 1900’s, is now the fastest growing protestant country with Pentecostalism as its source of largest growth. The continued importation of movements across Latin America primarily by the US includes the growing importation of contemporary Christian music with labels such as Hillsong and Vineyard spreading its prosperity gospel to a largely poor and frustrated audience of packed soccer stadiums and other mega centers.

Does this prove that Latinx are mostly conservative? Not at all. Countries like Chile, Argentina, Colombia, and Uruguay, which happen to be the most left leaning country not only in Latin America but perhaps in all the world second to perhaps New Zealand, continue to produce new art, new publications and most of all new theological thinkers that continue to challenge the narrative that all Latinx are conservative, passing very affirming LGBTQI laws both in the public life and in the context of the church.

The one thing we just might all have in common, even within our diversity, is the reality that oftentimes we are not taken seriously enough as part of the life and mission of the United Methodist Church to even be considered in the larger conversations and negotiations. In our national conversations around race, inclusion, and multiculturalism, our inability to move out of binary paradigms built by whiteness of either left or right, black, or white, male, or female or all the other ways we limit race and inter-cultural conversations to two choices, continues to limit all of us. As a community, we only seem to appear when we are needed to support an idea of inclusion and multiculturalism or to collaborate with other ethnic minorities as a commodity that helps to enliven our diversity within the church. That does not feel like inclusion, but rather tokenism.

So, the next time you hear someone say, “Latinos/Latinx are mostly” perhaps instead of sticking to a narrative that purports and assumes who we are and where we lean in this decision, maybe this is a great opportunity to ask yourself this: what makes you think you can create a narrative? In just that supposition alone, there might be some remnant of colonizing privilege inherent in the narrative that has been created about us itself that we need to confront before we go any further because the truth is we, Latinos/Latinx are just as diverse as you are, and with the same ability to surprise everyone. ¡Sorpresa!

Rev. Lydia E. Muñoz is an ordained elder in the United Methodist Church. She currently serves as lead pastor of Swarthmore UMC, in PA, and is an active member of MARCHA strategy team.

[1] Shereen Marisol Meraji, “Hispanic, Latino, or Latinx? Survey says…” NPR Code Switch, August 11, 2020. https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2020/08/11/901398248/hispanic-latino-or-latinx-survey-says

[2] Rodriguez, Jorge Juan V The Colonial Gospel in Puerto Rico. The Christian Century, January 3, 2017.

https://www.christiancentury.org/blog-post/practicing-liberation/colonial-gospel-puerto-rico